The Secret of Petra

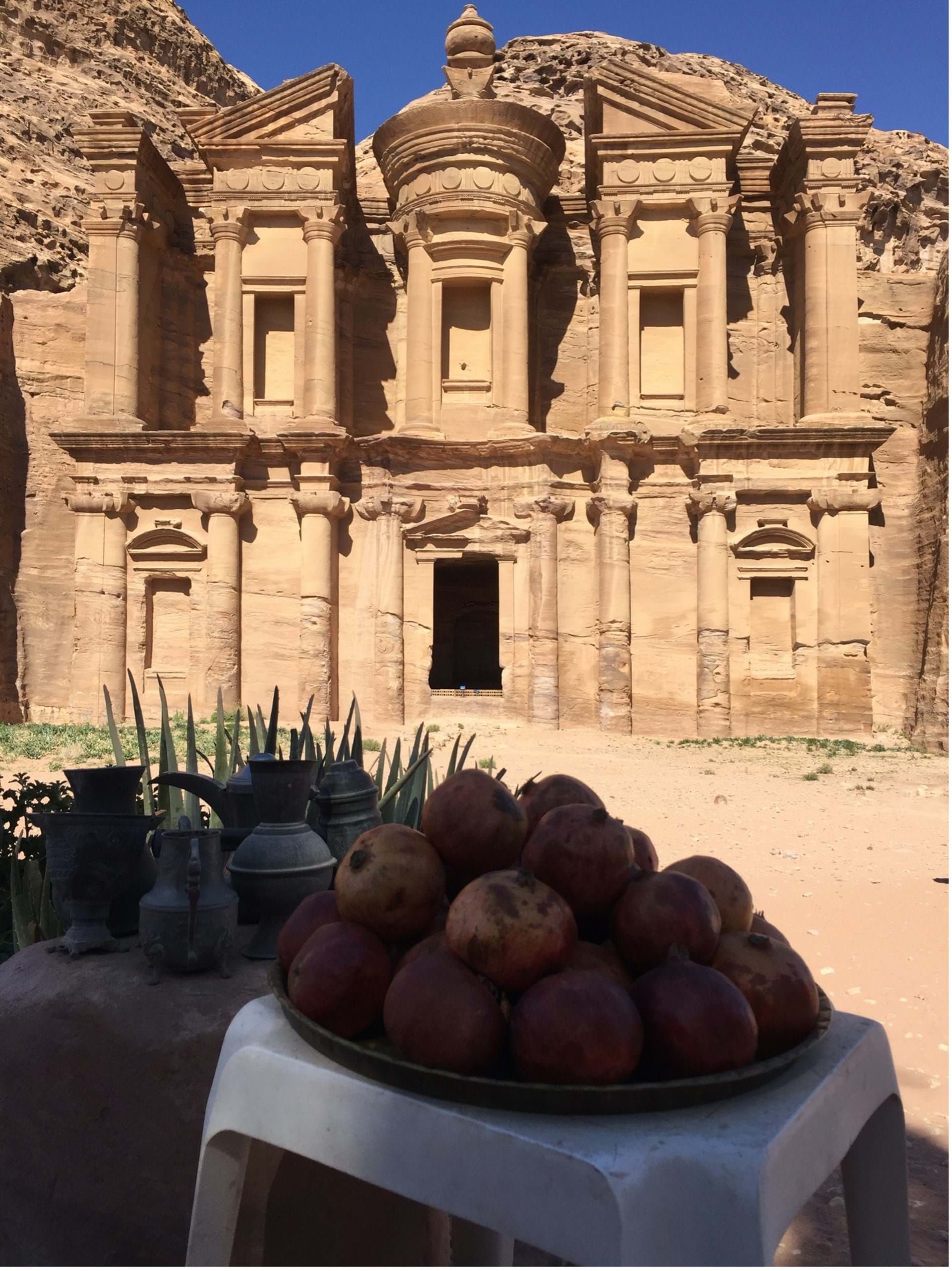

Petra in Jordan is a world-class destination for archaeological enthusiasts and history lovers alike, and a tour here is a truly unforgettable experience. Over the years, Andante Travels has pioneered innovative itineraries reaching parts of Jordan that other companies didn’t visit – until we did. We also led the way to changing how Petra should be best explored and came up with a simple solution – you need two full days there to do it justice.

Our best-selling Petra tour does of course feature two full days at the site itself, but other highlights range from a ride through the spectacular Wadi Rum desert in 4x4s to a float in the Dead Sea, and not forgetting visits to the well preserved Roman town of Jerash and the mighty 12th century Crusader castle at Kerak.

Nick Jackson, one of our renowned expert Guide Lecturers, can be found at the helm of our best-selling Petra – Jordan and the Desert Fortresses tour and he has revealed that while it is wonderful to take guests to this legendary site, there is one thing that most visitors don’t notice and he wants to point it out as it’s such an important aspect. On our Petra tours, it’s something you won’t miss. Here’s more from Nick Jackson.

“There is no more fitting a finale to an Andante Jordan and Petra tour than arriving at sunset ready to explore Petra. Despite the fact all guests are familiar with images of some of what they will experience the next day (and the one after that), the sheer majesty and mystery of this huge archaeological landscape and its peoples never fails to impress. But there’s more, including one smallish but beautiful thing, that very few visitors even notice. To me, it sums up Petra in one carved relief.

Who were the Nabataeans?

Though Petra has been studied and excavated for over a century, there is still much to discover. New and huge ritual platforms found recently beyond the downtown area hint at more city still hidden. Analysis of charred 6th century church documents has now completely revised the length of occupation of the site, and the excavation of mountain top villas has altered our understanding of the social structure of the Petra tribal elite.

There is still much to understand, not least those that created and inhabited this city of facades – the Nabateans themselves. How did the Nabateans transition from tented desert nomads to booming regional power with such a spectacular capital as Petra in a few short centuries?

On the face of it, one thing is obvious, the Nabateans were a flexible and successful folk, absorbing influences from an area as wide as they controlled, travelled to and traded with. This can be studied most readily during our visit through Petra’s architecture, where foreign but familiar cannons appear amongst the unique Nabatean style. Familiar, at least, at first glance.

Nabateanology has been illuminated through excavations but also other archaeological channels. Linguistic grouping derivations, ancient written sources and inscriptions, and numismatics from the Nabatean Golden Age (1st century CE).

But still this desert people are a mystery, like the view of a camel caravan, seen from cliffs of Rum, figures discernible but still shrouded in clouds of red sand and dust.

The name by which they called themselves was Nabatu. This seems to have connotations of those that manage/ channel water, very apt as we see graphically on display at Petra. This fits snugly with some of our early written sources, namely Diodorus and Strabo, who forward the idea that the original Nabateans were a coalition of Arabian desert peoples banned from traditional oasis and thus forced created their own, hidden, cistern systems throughout the desert.

There have been efforts to place their origins way beyond their later homeland, which stretched broadly from Damascus to the Negev, to the gulf of Aqaba and into NW Arabia, with its desert gateway city, Hegra. Linguistically, Nabatean inscriptions belong to the family ‘Aramaic’. This was a descendent of Mesopotamian Semitic languages and a cuneiform script, Akkadian, used for international communications for millennia throughout the near and middle east and Egypt during the Bronze Age.

Aramaic crystallised as a lingua franca towards the end of the second millennium BCE. The Phoenician alphabet grew from it, Palmyra spoke a version, Israel and Judah use(d) a variant and crucially it was absorbed as the official speak of the new Iron Age imperial power brokers – Assyria and Babylonia.

Perhaps most importantly here, it is from Nabatean Aramaic that Arabic would descend.

Where did the Petra we visit come from?

We are on more solid ground searching for the Nabateans when we look at the geopolitics of the Old Testament Iron Age (1st M BCE). The world of Israel, Judah, Ammon, Moab and Edom. The southern borders of Edom would have been the interface where nomadic Nabateans met the settled Iron Age Holy land. Petra proper, and several other strategic sites in the area, were initially Edomite settlements. The relationship between Edom and the Nabateans seems to have been more peaceable than with its immediate western neighbours (‘Over Edom I will cast out my shoe’ Psalm 60).

The 6th century BCE Babylonian sack of Jerusalem allowed Edomites, who might well have allied themselves with Nebuchadnezzar, to move west and control more of the areas where the hugely lucrative Arabian trade routes cut through the Negev desert fringe to the Mediterranean. The origin of this trade was increasingly controlled by the Nabateans.

Babylonian rule disintegrated Edomite influence over her old southern border, and by the 4th century BCE Nabateans controlled Petra – making it a safe, mountain top, well-watered depot at the end of their strenuous desert crossings. Its new name was Rakmu.

As Hellenism replaced the power of Persia as the regional controlling force in the 4th century BCE, and itself started to fragment in the 3rd century, it was then the Kingdom of Petra was carved out, and the city built from the living sandstone. Imagine, just about everything we see in Petra was created in less than 200 years.

What were the factors driving this change? Income and a chance to increase regional power and therefore increase income was perhaps among the most significant.

There are several observations on Nabateans running through classical authors accounts, and here we need to add Josephus, a contemporary source. Still seen as the ‘other’ by the Hellenised and Roman east, a few Nabatean practices strike our sources as odd. Burial customs and hearsay talk on male and female relationships for example.

Descriptions of the structure of the elite, for instance, tell that the ‘King’ served his guests (something that is entirely acceptable, even required, for the honour of a host in today’s Bedu societies) but raises the Hellenistic eyebrow. This fits well with the traditional nomadic origins of the Nabateans themselves.

As the Nabateans absorbed more foreign influences, the hospitality and tribal structure aspect of their culture they kept. Other aspects they allowed to change.

All sources agree on one thing though, Nabatean business acumen was an essential trait, as was their keenness to increase wealth. Taking advantage of collapsing Seleucid control and the resulting chaos caused by the Maccabean revolt, Nabateans seized control of significant chunks of Jordan, southern Syria and Israel.

It was this that led to a massive reorganisation of Petra and a rapid increase in the complexity of the Nabatean socio-political, economic and cultural world. Petra grew into a permanent centre for administration and defence of this new kingdom, and the royal home of the Kings and Queens that headed it, during life, and after.

The God Block

In 106 CE, Petra was formally absorbed into the Roman Empire. Its independence gone, life in the city continued into the Christian period, just under a new administration, familiar to it for over a century before.

Much evidence of the influence of Nabatean contact with the cultural worlds mentioned in this story – from Nebuchadnezzar to Hadrian – can be seen absorbed into Petra’s face. Some monuments, like earliest tomb facades or the ‘Monastery’ reflect a Nabatean style; strong, clean, simple and strangely ‘modern’. Others, like the ‘Treasury’, show an admiration for the classical, and in fact might have had Hellenistic architects involved in the creation.

Four huge earthquakes, spread over 5 centuries, eventually tumbled urban Petra. The thrust of modern excavation and reconstruction has been directed on temple buildings. The Petra cliffs, strewn with tomb façades, from the simple trapezoidal to elaborate classical styles, might give the visitor the impression it’s a funerary city. Because of these two factors, much ink has been spilt pondering Nabatean religious and burial practice.

The gods and deified rulers worshipped in the temples also show the influences on the Nabateans. Edomite Qos, Egyptian Isis, Syrian Baal and Atargartis and a slew of Arabian sub deities were all worshipped alongside Dushara and Allat, the male and female figure heads of the pantheon.

The way the Nabateans displayed their deities was through the ‘God Block’, a simple rectangular stele, often within a niche. All through the famous Siq – and carved into countless high places and shrines throughout the Petra landscape – these blocks – bethels lit. ‘house of god’ – can be seen. The Nabateans knew them as ‘places of prostration’.

They come in clusters or alone, some bigger than others, some originally bejewelled, some bearing representations of heavenly bodies. Some have only eyes, some a face.

As Petra developed – they changed also. Under Greco-Roman influence, the deities became anthropomorphised.

This is a huge cultural leap. Perhaps a leap too far?

Archaeology Tours

NEWSLETTER

Opt-in to our email newsletter and hear about new offers first – view our privacy policy for details.